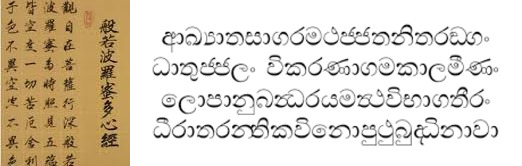

Introducing Pāli and Buddhist Literary Chinese

Since RYI will conduct

Pāli

and Buddhist Literary Chinese in the coming Summer Program, I am happy to introduce

these languages here, which I have studied before. In my opinion, the most

difficult language to study is Chinese since there is no alphabet in Chinese

characters. In other words, to read Chinese, we need to memorize each distinct

character. From grammatical aspects, nouns and adjectives which do not inflect

for case, definiteness, gender make Chinese is more challenging and difficult

to comprehend. Moreover, verbs do not inflect for person, number, tense,

aspect, or voice. To study Buddhist literary Chinese, usually students are

firstly guided from the basic Classical Chinese text, such as Sanzijing.

Pali and Sanskrit are

very closely related and the common characteristics of both languages are

easily recognized. In fact, a very large proportion of Pali and Sanskrit

word-stems are identical in form, differing only in details of inflection. Pali

nouns inflect for three grammatical genders (masculine, feminine, and neuter)

and two numbers (singular and plural). The nouns also display eight cases:

nominative, vocative, accusative, instrumental, dative, ablative, genitive and

locative case. However, in many occasions, two or more of these cases are

identical forms; especially the genitive and dative cases. The Pali grammar has

rich nominal declension and usages of compound nouns. The Pali language

includes six tenses (present, future, imperfect, aorist, conditional, and

perfect) and outlines two types of voices: active and reflective. Pāli

are written in few scripts, mainly in Singhala, Khmer, Burmese, Thai, Devanāgarī,

and Roman. If we have studied Sanskrit, it will be much easier to approach Pāli.

Welcome to study Buddhist

Literary Chinese and Pali! I rejoice on the opening of these new courses in

next summer program. Hopefully you guys enjoy studying these languages at RYI!

Comments